Release Date: June 27, 2001 Developer Name: Ion Storm Dallas

You probably remember the name Ion Storm for two reasons: the masterpiece that was Deus Ex and the… let’s call it “ambitious” marketing campaign for Daikatana. But sandwiched between those two behemoths was a weird, chunky, neon-soaked fever dream called Anachronox. It’s a game that had no business working as well as it did, yet twenty-five years later, it remains one of the most uniquely charming experiences in the medium. It’s a love letter to the 16-bit JRPG era, written in the Quake II engine by a bunch of Western developers who clearly had a lot of coffee and very little supervision.

The Low-Rent Noir of the Future

The game introduces us to Sylvester “Sly” Boots, a private investigator who is roughly one bad day away from living in a cardboard box. Sly isn’t your typical RPG protagonist; he’s a washed-up loser with a mounting debt and a penchant for getting punched in the face. He operates out of a dumpy office in the slums of Anachronox, a gravity-defying planet that looks like someone threw a futuristic city into a blender and forgot to put the lid on. The aesthetic is pure cyberpunk noir, but with a sense of humor that prevents it from ever becoming too self-serious.

What makes the world of Anachronox so special is its grit. This isn’t the shiny, pristine future of Star Trek. It’s a place where things break, people are rude, and the galactic stakes are often overshadowed by the fact that you need to find enough change to pay your bar tab. The writing is snappy and genuinely funny, leaning heavily into the “buddy cop” dynamic as Sly assembles a ragtag team of misfits. You aren’t just saving the universe; you’re doing it with a team that includes a cynical robot, a miniature planet named Democratus, and Sly’s dead secretary, who exists as a digitized hologram inside his PDA.

A Love Letter to Chrono Trigger

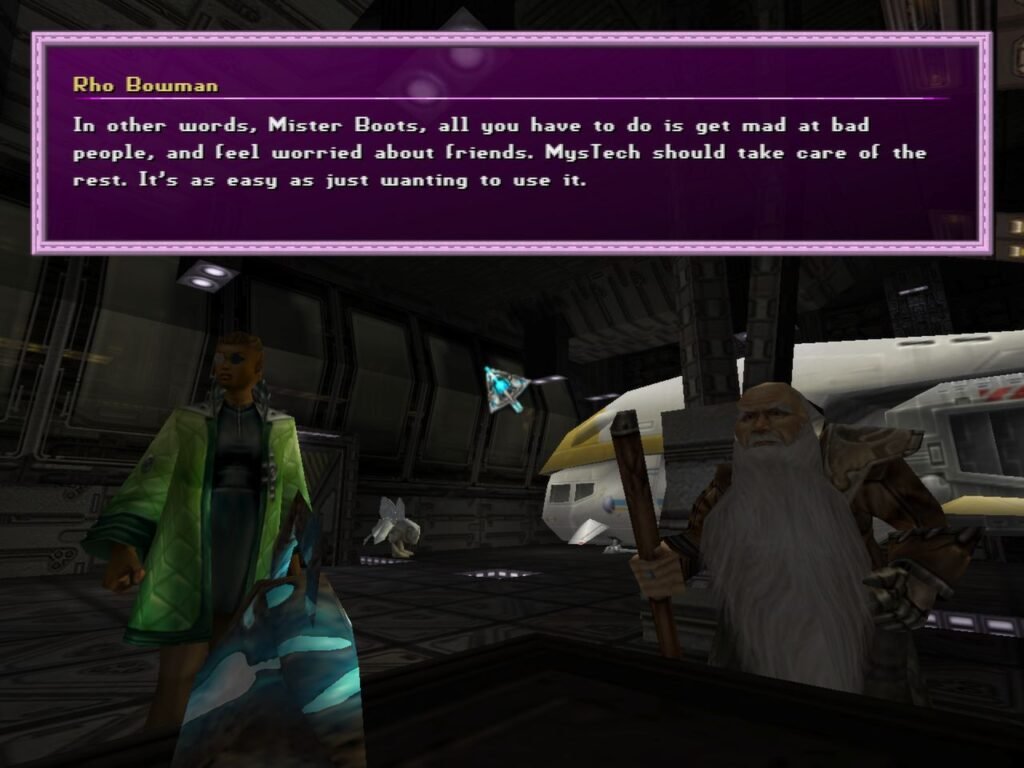

While the aesthetic is sci-fi, the soul of Anachronox belongs to the Super Nintendo. The gameplay is a blatant, unapologetic homage to Chrono Trigger. It uses a variation of the Active Time Battle system, where you wait for meters to fill before unleashing attacks or “Mystech” abilities. It’s a bold move for a PC game of that era—most Western RPGs at the time were leaning toward the complex, stat-heavy isometric views of Baldur’s Gate or the first-person immersion of System Shock.

However, Anachronox makes it work. The combat is snappy, and the cinematic camera angles during special moves give it a flair that static sprites simply couldn’t achieve. The “Mystech” system adds a layer of customization that feels like a precursor to the materia systems of Final Fantasy VII, allowing you to slot different powers into your gear. But the real star isn’t the math; it’s the choreography. Watching a giant planet-sized party member shrink down to human size to participate in a three-on-three brawl is the kind of visual gag that never gets old.

The Engine That Could(n’t Quite)

Let’s talk about the elephant in the room: the Quake II engine. By 2001, the id Tech 2 engine was already showing its age. Anachronox is famously blocky. Characters have hands that look like loaves of bread, and the environments, while creatively designed, can feel a bit claustrophobic and jagged. Yet, Tom Hall and his team at Ion Storm managed to squeeze an incredible amount of personality out of those polygons. The facial animations, though primitive by today’s standards, are surprisingly expressive. Sly’s “I’m too old for this” eye-rolls and the quirky idle animations of the NPCs give the world a “lived-in” feeling that many modern, high-fidelity games fail to capture.

The trade-off for the aging tech was the cinematic direction. The game is packed with cutscenes that use the in-game engine to tell a sprawling, epic story. Because the developers didn’t have to worry about pre-rendered CGI budgets, they could afford to be weird. They could spend five minutes on a joke about a sock or a bizarre side quest involving a museum of futuristic artifacts. This freedom allowed the game to have a pacing that felt more like a serialized TV show than a standard “go here, kill ten rats” RPG.

Why We Still Care About a Half-Finished Masterpiece

The tragedy of Anachronox is that it was meant to be the first part of a larger story. The game ends on a massive cliffhanger that, due to the closure of Ion Storm Dallas shortly after release, will likely never be resolved. It’s a “Part One” in a world where “Part Two” doesn’t exist. Usually, that would be a death sentence for a narrative-heavy game, but Anachronox is so rich with world-building and character development that the journey remains worth it even without a final destination.

It’s a cult classic in the truest sense. It’s a game that succeeded despite its technical limitations and its botched marketing. It’s a game that prioritized character and humor over photorealism and “edginess.” When you play it today, you aren’t just playing an old RPG; you’re stepping into a specific moment in time when developers were still figuring out how to tell cinematic stories in 3D spaces. It’s messy, it’s blocky, and it’s occasionally frustrating, but it has more heart in its pinky finger than most AAA titles have in their entire campaign.

If you can get past the chunky 2001 graphics and the lack of a sequel, you’ll find a game that is genuinely hilarious and deeply imaginative. Sly Boots might be a loser, but his debut (and finale) is nothing short of a win for anyone who loves a good story.