Release Date: June 27, 1996 Developer: LucasArts

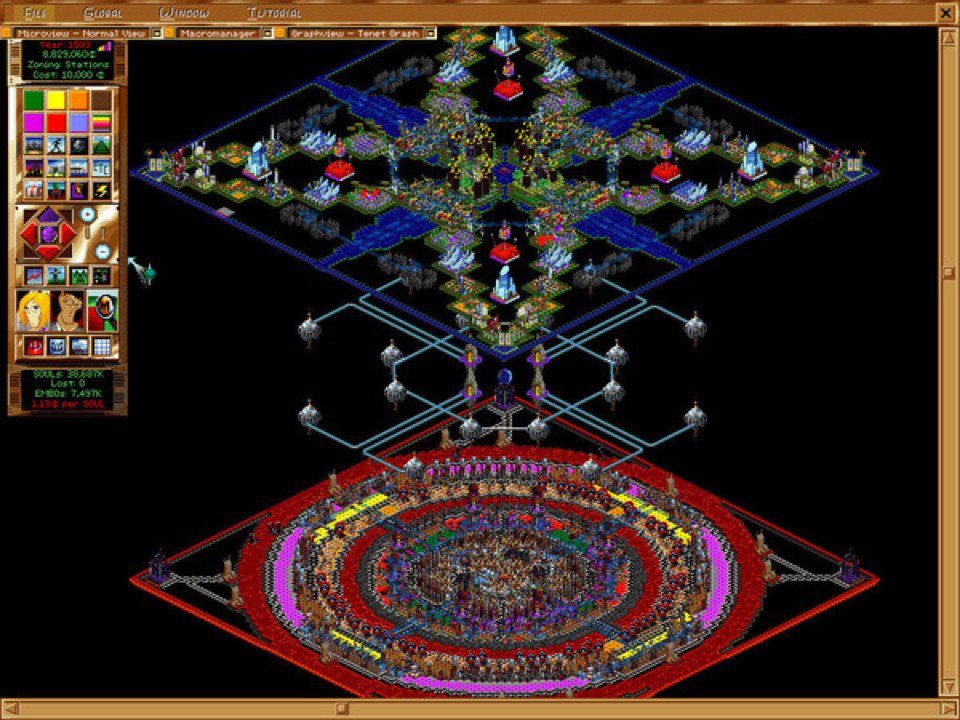

In 1996, while the rest of the gaming world was preoccupied with the rise of 3D shooters and the burgeoning RPG craze, LucasArts released a game that was, quite literally, out of this world. Afterlife was a satirical, incredibly complex “god sim” that tasked players with managing the ultimate duality: Heaven and Hell.

Marketed with the classic LucasArts wit, the game didn’t just ask you to build a city; it asked you to manage the eternal fate of an entire planet’s population.

The Demiurge’s Dilemma

In Afterlife, you play as a Demiurge, a cosmic bureaucrat appointed by “The Powers That Be.” Your job is to manage the spiritual infrastructure for the inhabitants of a distant world known simply as “The Planet.” These inhabitants are called EMBOs (Ethically Mature Biological Organisms). When an EMBO dies, they become a SOUL (Stuff Of Unending Life) and head to your neck of the woods for their eternal reward or punishment.

Unlike SimCity, where you worry about power lines and police stations, Afterlife revolves around the Seven Deadly Sins and the Seven Heavenly Virtues. You must zone areas for specific fates—like Pride, Avarice, or Lust in Hell, and their counterparts like Humility, Charity, and Chastity in Heaven.

Juggling Two Realms

The game’s greatest challenge is the requirement to manage both planes of existence simultaneously. Each realm has its own set of rules:

- Heaven: The souls here demand efficiency and aesthetic beauty. They want short commutes to their rewards and a diverse mix of virtues nearby. If Heaven becomes too monotonous or “vibes” turn sour, the souls become restless.

- Hell: In a brilliant mechanical twist, Hell operates on misery. The damned souls are supposed to be unhappy. To keep Hell functioning correctly, you are encouraged to build inefficient, winding roads that force souls to trek through fire and brimstone for as long as possible.

Helping you navigate this chaos are two iconic advisors: Aria Goodhalo, a perky, soft-spoken angel, and Jasper Wormsworth, a cynical, chain-smoking demon in a business suit. Their banter provides much of the game’s charm, though they aren’t afraid to resign if you let the budget—measured in Pennies from Heaven—fall into the red.

A World of Complexity

Beneath its goofy exterior, Afterlife is notoriously difficult. It introduces layers of micromanagement that would make a modern strategy game blush. You have to:

- Manage Beliefs: EMBOs on the planet hold different religious tenets. Some believe in reincarnation; others believe in a “Heaven-only” or “Hell-only” afterlife. If you don’t build to match their beliefs, souls will simply drift away into the void, taking your revenue with them.

- Training the Workforce: You can’t run an afterlife without staff. You must build “Topias” to house angels and demons and training centers to educate them. Relying on “imported” workers from other afterlives is a quick way to go bankrupt.

- Survive “Bad Things”: Instead of Godzilla or fires, your realms are threatened by surreal disasters like the Disco Inferno, Hell Freezes Over, and the Heavenly Nose (a giant nose that snorts up buildings).

A Cult Classic Legacy

Afterlife remains a singular entry in the simulation genre. It captured the “Experimental LucasArts” era perfectly—a time when the studio was willing to take a high-concept, philosophical premise and turn it into a deep, pun-filled strategy game. While it was criticized at the time for being perhaps too complex for its own good, it has since earned a dedicated cult following. It stands as a reminder of a time when simulators weren’t just about building—they were about world-building in the most literal, cosmic sense.